Of all the newsletters that cross my desk, the one that tugs my heart comes from the Friends of the San Luis Valley National Wildlife Refuges. That heart-tug pulls back to my youth there, hunting rabbits and ducks on that land when it was wetlands and grassland, long before it was a nearly-dry refuge pumping groundwater to maintain some of its habitat. The two refuges cover about 17 square miles of the 8,000-square-mile San Luis Valley of southern Colorado, at a 7600 foot elevation surrounded by high mountains.

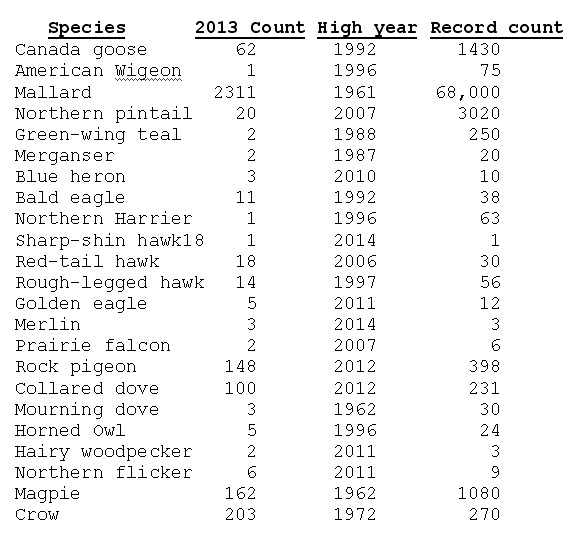

The Feb 2014 newsletter featured the annual Christmas bird count. I’ll invite you to scan down, comparing the 2013 count with the record high count. Maybe 2013 was a bad season, but I’ll offer a more penetrating insight below.

——————————————————————————————————–

I notice crows and pigeons are doing well. Crows and pigeons live well with humans and garbage. I remember no crows in the valley during the 1940’s; I had to ask my dad about crows. He grew up in Illinois, and told me crows never mistake the difference between a fishing pole and a gun.

The chart indicates magpies are doing less well. I remember magpies everywhere as a youth. The invasive collared dove has replaced the mourning dove where I now live, and apparently also at the refuge. The published chart includes counts of 18 additional species, including the red-wing blackbird, of which 11 were seen in 2013 but 5111 were counted in 1996.

But what about the ducks? Sixty-eight thousand mallards in 1961? Yes, that’s credible. In the 1940’s, we would go to the edge of town in the early evening, seeing dark clouds of ducks twenty miles away on their daily migration between the wetlands and the feed. The old-timers told this boy that in their time (about 1900), the ducks would blot out the sun, and in places the grass could hide a man on a horse.

So what?

It’s apparent that the wildlife is drastically diminished despite the establishment of the wildlife refuges in 1953 and 1962. Maybe that’s because the groundwater that supported the vegetation and wetlands has been mined. But there’s a broader story than the loss of the birds. It’s how we regard these things.

In October of 2013, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service published a 365-page report on refuges, entitled, “Banking on Nature, The Economic Benefits to Local Communities of National Wildlife Refuge Visitation.” The report finds that national refuges return $4.87 to local economies for every $1 congress provides in funding. Furthermore, refuges generate $2.4 billion in sales and economic output, create 35,000 jobs annually, and generate $343 million on local, state, and federal taxes.

Isn’t that a wonderful? A $4 return for a $1 investment! Might the refuges generate an $8 return if they still had the ducks? I suppose the Fish and Wildlife Service must perform such analyses to justify its existence to a congress that understands dollars, not ducks. But there’s the tragedy. In our society, the value is the return on investment, not on return of the ducks.

The question.

Why can’t a wildlife refuge be valued as providing a small, remaining place for wildlife? Why must it be justified by dollar return? Life is a process of collecting experiences. Unfortunately, our society regards life as a process of collecting monies. What’s life worth living for, existing in, experiencing, sharing? Where are our values? Didn’t Socrates say an unexamined life is not worth living? Ah, perhaps these unasked questions are more of that elephant in the room.