Ever think of inflation as a tax on the lower classes, a tax programmed to benefit the wealthy?

We all live with inflation. Almost everything—particularly essentials—cost more each year. Remember when a cup of coffee or an ice cream cone cost 5¢? If so, you’ve seen a few decades go by.

With income tax, the larger your income, the greater is your tax rate. In comparison, inflation is like a special tax wherein the less income you have, the more you are taxed. How does that work?

Well, the lower your income, the greater fraction of it you must spend for essentials—food, rent, transportation, energy. If you have a low income the essentials take all of it, so there’s little left over for investment in a home, savings for education, a cushion for medical expenses, a job change or pleasures. At the other end of the income scale, a wealthy person might have a high income from a management position and income from investments in stocks, property, or businesses. If food and living expenses rise by 2.5%, it would not restrict daily choices. The essential costs of living might be the same for both parties, but the impact of inflation is much stronger on the working wage earner, even if wages rise each year. Furthermore, wages often do not match inflation.

The wealthy often invest in property, banking, and corporate business—items with value and dividends that often precede and exceed inflation. Large corporations and the wealthy often benefit from inflation.

Inflation comes from the insertion of more money into the economy, often when the Federal Reserve maintains a low rate at which banks can borrow. Banks in turn loan several times their borrowings to businesses and home buyers, thereby creating money. New money stimulates the economy as measured by the Gross Domestic Product, which does not always mean money in the pockets of wage earners. The new money might instead bid up the price of real estate, for example.

Let’s try an example. Suppose that inflation and salaries happen to rise together. Suppose a working person with a family is paid $40 thousand per year, while a rich person’s investment and earned income combined are $4 million per year. Suppose both incomes increase by 2.5%. The working person’s annual income rises by $1000, about equal to the rise in his/her family’s food and rent costs. The rich person’s income rises by $120,000, perhaps $119,000 more than the rise in essential costs. The rich person can invest that difference to make additional gains in subsequent years. Money makes money.

So what is inflation?

The common measurement, called the Consumer Price Index (CPI), is the decrease in the purchasing power of currency due to a rise in prices of a selected set of goods and services. This might be measured across the country or at a given location; for a year, or other time interval. Note the CPI measures the change of prices over a chosen interval of time.

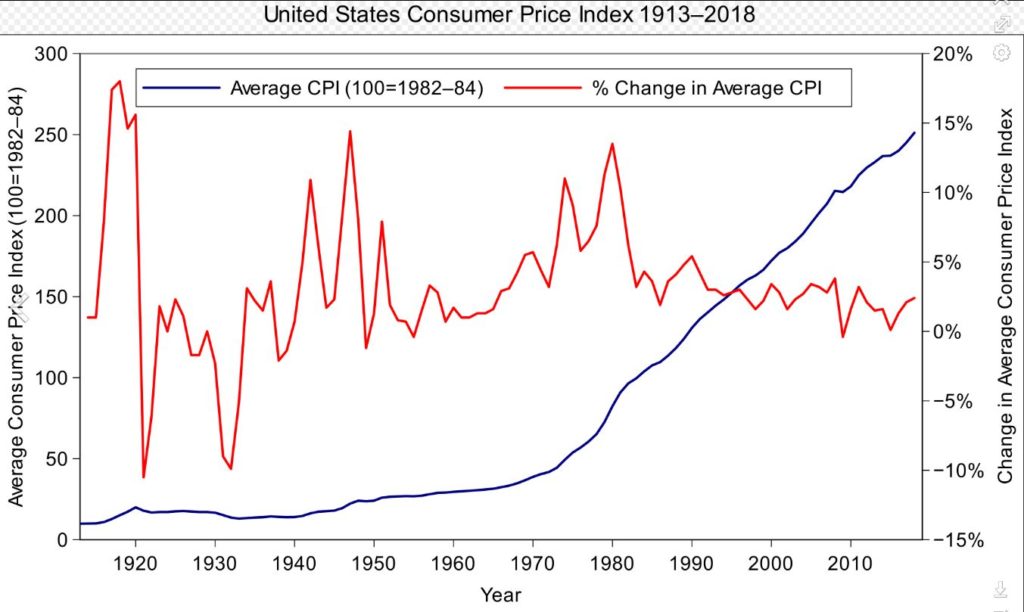

The graph below plots the annual national CPI from 1913 to 2018. The blue curve (values on left axis) compares what the set of goods and services would cost you at each year, assuming you bought $100 worth in 1984. What cost about $30 in 1970 and cost $100 in 1984 is priced at $250 in 2018. The red curve (values on right axis) is the annual percent change in price each year.

Of course, the inflation you experience depends on exactly what you buy. During the 12 months preceding February 2019, the change in CPI was 1.5% on all items, 2% on food, and –5% on energy.

That’s funny. I didn’t notice that the price I paid for a gallon of gasoline went down 15¢.