The lawsuit

A year ago, the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia dismissed a lawsuit brought by an Alabama businessman Shaun McCutcheon and the Republican National Committee (RNC). McCutcheon, who owns a firm that develops coal mining and electrical generation, appealed to the Supreme Court, claiming that the Federal Election Campaign Act (FERC) restricted freedom of speech. That law limits the total contributions to political candidates, PACs, and party committees by individual persons. On October 8, 2013, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments.

Why not?

In Blog 20, I described the similar 2010 Citizens United case, in which the Supreme Court decided that corporations could make unlimited political donations. As you would expect, citizen’s groups like Common Cause and Public Citizen are alarmed at the McCutcheon/RNC follow-on to Citizens United. (Many states, localities, and congresspersons support a constitutional amendment to overthrow Citizens United.) Unlimited (or nearly unlimited) ability to pay political candidates forms a positive feedback system in which money buys governmental favors, which in turn enable the buyer to make more money with which to buy more favors, leading to government by money and the ultimate collapse of democracy into fascism.

This concern is widely expressed on the internet, is reported on public TV, and gets at least a one-time mention in a few national newspapers. Why isn’t this on the front page of magazines and newspapers? Is it because the rich control the media, or is it because most folks don’t care?

For a dispassionate summary, see the Federal Election Commission’s case summary. For discussion that ought to be reflected in every newspaper see, for example, Bill Moyers review, The Huffington Post, The Washington Post, and Common Cause.

Help from a senator

As usual, the Supreme Court allowed an hour for oral arguments. It is curious that Senate minority leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) was given ten minutes of that hour to argue that all campaign contribution limits should be eliminated because any limit infringes on free speech. If free speech is the issue, why was McConnell given time to argue, but I was not? It is clear that freedom is more available to the rich and already-powerful. McConnell wasn’t even a party to this lawsuit, but he has a history of opposing citizen interests. Ten years ago, he challenged the McCain-Feingold campaign finance reform in the Supreme Court.

Crazy logic

There’s crazy logic here. Although his buddy Senator McConnell asks the court to remove all limits, McCutcheon doesn’t ask to raise the limit for a donation to a single candidate, but he wants to allow one donor to donate to an unlimited number of candidates. Let’s look at that. Why should a resident of Alabama be allowed to make any donation to a congressional race in Iowa or New Mexico? The true issue isn’t that the present limits are too restrictive. They’re too lax. If anyone, anywhere, can insert huge money into any political campaign, the citizens in effect have no voice. The present system is corrupt by allowing remote donations to political decisions in which the donor could not register to vote. That is a restriction of more than free speech. It’s disempowerment. McCutcheon and the Republican National Committee seek to extend that disempowerment.

Want clarification? Public Campaign offers a very brief summary of the whole thing, and a full legal review is in the Supreme Court blog.

—

Contribution Details: The Biennial Limit

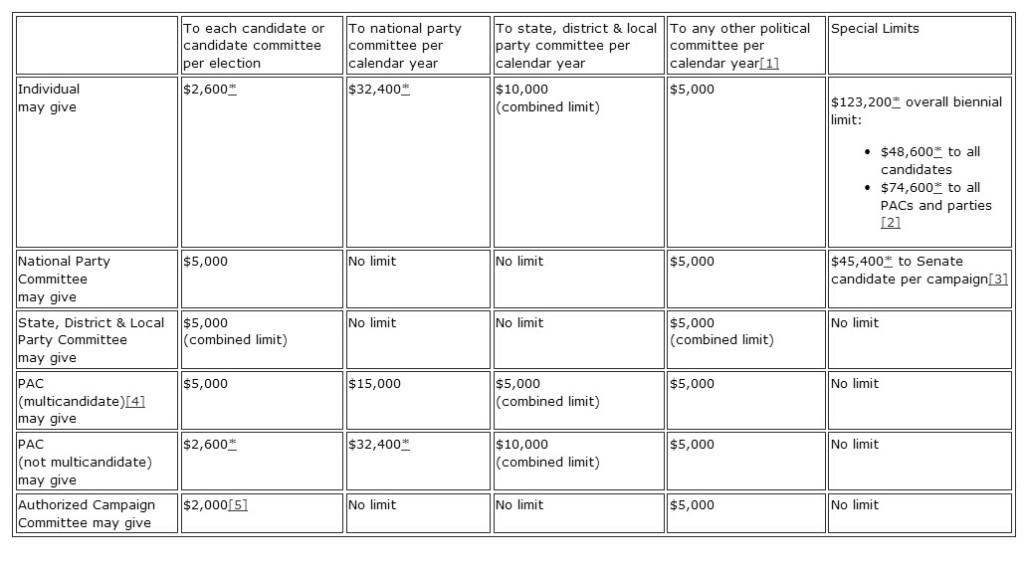

For those who want details, I’ll paste the current political contribution limits below, copied from the Federal Election Commission brochure.

As an individual, you are subject to a biennial limit on contributions made to federal candidates, party committees and political action committees (PACs). The limit is in effect for a two-year period beginning January 1st of the odd-numbered year and ending on December 31st of the even-numbered year. The biennial limit is indexed for inflation in odd-numbered years. The 2013-14 limit is $123,200.

This limit includes up to:

- $48,600 in contributions to candidate committees; and

- $74,600 in contributions to any other committees, of which no more than $48,600 of this amount may be given to committees that are not national party committees.

Within this biennial limit on total contributions, an individual may not exceed the specific limits placed on contributions to different types of committees, as illustrated in the chart. Values are adjusted every two years for inflation.